Build and Sustain Your Records Program with a Records Management Playbook

What if your organization’s entire records team won the lottery today and quit? What would happen to your records program? How long would it take your organization to rebuild the team from scratch? If you had a records management playbook in place, your newly hired team could hit the ground running!

What is a Playbook?

In sports, a playbook describes the “plays” a team executes to accomplish its goals and objectives—generally, winning a game or match. Plays are tailored to specific circumstances: the team’s personnel and capabilities, the opponent’s capabilities, and the specifics of the in-game situation. Some plays just do not come up very often, while others are executed regularly throughout the game. Some plays only come up at the end of a period of play or towards the end of the game. And once the game is over, the coaching staff reviews the plays and the team’s execution of them and makes changes to get ready for the next match.

Similarly, a business playbook describes the plays that a particular organization, department, or work process executes to accomplish its goals and objectives. Larger or more mature organizations might have multiple playbooks, while smaller or less mature organizations might have everything in a single playbook.

In this article, we will focus on the records management playbook—the list of plays that a records program will execute on an ongoing basis. Different records programs will operate at different levels of maturity, so some programs will include more plays in their playbook than others. Similarly, different organizations have different cultures, and the playbook needs to reflect those realities as well.

So how is this different from a standard operating procedures (SOP) manual? The playbook is like an SOP in that it lists the things to be done and some detail about how to do them. But plays go beyond just the tasks and activities required to include things like metrics, references, and key players. It also includes cultural values and mechanisms for making decisions when the play is not so clear-cut. We will look at the structure of the playbook and the plays in more detail later in this article.

It is also the case that in many organizations, SOPs were written years or even decades ago. Because they tend to be scattered around the organization, they are not maintained well; and because of that, there is often a significant divergence between what the SOP says in describing a process and how that process actually gets done. Again, the playbook can provide value by having everything in one place and in a readily maintainable format.

Through a playbook, the organization can:

- Identify and implement best practices and standards

- Ensure that operational practices are consistent, repeatable, and standardized to the extent possible

- Ensure resources and priorities are aligned to common goals

- Train new employees to perform within the guidelines, become a part of the desired culture, and develop shared values

- Ensure that important expertise, on which their business results depend, does not walk out the door when employees are unavailable, transition to a different role, or leave the company

The records management playbook’s objective is to provide best practices for the records program, not to substitute for management and leadership. It is critical to balance the importance of standards and guidelines with the value of local management discretion and individual employee creativity[1].

Another way to look at the records management playbook is that it contains what someone would need to know to execute the various tasks required to sustain the records management program over the course of thirty, sixty, or ninety days—even up to a year. What are the things you do, create, monitor, or report regularly? What are the questions you answer every day or every week? These should be in your playbook.

The playbook is a living document. As the team develops new processes, they should be turned into plays and added to the playbook. As the team updates, streamlines, or adds processes to reflect changes in the organization, its technology, or legal or regulatory requirements, the team should also update the plays in the playbook. The playbook thus becomes the sole source of truth for all things involved with and related to your records program.

What the Playbook is Not

At the same time, the playbook should reflect the reality of what is done and how it is done. It makes no sense to write a play about disposing of legacy emails if legacy emails are not in fact being disposed of. In other words, it is not a list of best practices and the ideal world if time and resources were no object. Rather, your playbook should be accurate as to what you are currently doing, and as your program matures, those changes should be reflected in the playbook.

It is also not a list of how some other organization does things. A different organization, even in the same industry and jurisdiction and similarly sized, will have a different level of maturity, different organizational culture, and different personalities involved. It might be helpful to look at another organization’s records management playbook for ideas and completeness, but you should not try to implement its playbook as-is in your organization.

This also means that plays should include some amount of flexibility, because things change, and sometimes the circumstances require that a play be executed differently. Inflexible adherence to whatever is described in a particular play may miss something and will tend to encourage employees to ignore it. Again, with effective leadership and management, this sort of flexibility should not be a major issue.

Similarly, it is helpful to distinguish between plays that are executed on some sort of a regular basis, with projects which may be executed much less frequently. For example, how often will you change recordkeeping applications? You probably don’t need a “Select and Implement New Recordkeeping Application” play in your playbook. You need a process to follow, to be sure, but that is not a play.

The Benefits of Using a Records Management Playbook

The benefits of having and using a records management playbook include[1]:

- Organization: The playbook includes all the information your records management team needs to operate successfully, in one organized and easy-to-access place.

- Efficiency: The team can save time when they have questions about workflows or procedures because the answers are in the playbook. They can follow the steps outlined in the document rather than searching through numerous files, locations, and resources to find information. And if it is digital, and why wouldn’t it be, supporting resources can be linked directly within the play.

- Work quality: The playbook includes references, standards, checklists, and templates that align with the organization’s existing policy and quality frameworks. Work output will become better and more consistent as a result.

- Employee training: A playbook makes it easier to onboard new team members and roles and helps them get up to speed quickly.

- Independence: Employees can refer to the playbook instead of asking their managers for help for those plays that are included in the playbook. Similarly, supervisors can trust their employees to do quality and accurate work without constant management because they have a playbook for guidance.

The Structure of the Records Management Playbook

The records management playbook is intended to be self-contained; that said, there is a tradeoff between being comprehensive and being unwieldy, especially for an organization with a mature records management program. In that case, it makes sense to focus only on the plays, and move the other elements listed below into supporting documentation. It may even be worth breaking the playbook into two or more parts—for example, records management processes and records program processes.

Depending on how you build and publish your playbook, it may make more sense to link to your supporting documentation—the detailed procedures, checklists, flowcharts, standards, and anything else that supports a particular play.

The playbook will have three distinct parts: the introduction, the actual plays, and any appendices.

The Introduction

This entire part should be brief—no more than a page or two for each section, and shorter is better. Some organizations leave this section out entirely and make this content available as a separate, supporting document. The introduction, if included, should set the stage for the playbook. It could include any of the following sections.

Introduction to the playbook. Much of this is included in the first section of this article.

Introduction to the records management program. This should introduce your records management program: its purpose and how it supports organizational outcomes. It should also outline any unique aspects of how your records management program works within your organization—for example, unusual administrative or reporting requirements. Again, will often vary for different jurisdictions or industries.

Organizational context. This helps to orient new staff to the organization and the plays in the playbook. This section would include:

- Organizational mission: What does your organization do, and what does its legal and operational environment look like? These can help those reading the playbook to have some additional context over why the plays are the way they are. For example, a law firm’s records program must deal with client records, while a government agency’s may have to deal with Freedom of Information or open records-type requirements.

- Organizational culture: Is your organizational culture more focused on reducing and managing risk, or on accepting reasonable risks that are relatively low impact? Do you encourage people to be creative, or to follow directions closely? Again, these can shape the granularity and level of detail in your plays.

- Definition of roles and responsibilities: These are the roles involved in the execution of the records management program, directly and indirectly, and who would be included on a RACI (responsible, accountable, consult, inform) chart. A large and mature records management program might include the following individual roles: director of records management, records manager(s), records analysts, and/or records coordinators. It might also include some sort of a steering committee. A smaller or less mature records management program might have a single person, with a non-records related title, or even be a part-time role. Indirect roles might include those with which records management team members need to collaborate, such as IT, or whose approval is required under certain circumstances such as Legal signing off on policy changes.

The Plays

There are hundreds of potential records management plays that could be included in a records management playbook, and there are certainly many more that would be unique to jurisdictions and industries. But as noted earlier, the playbook should contain the plays that the organization actually executes. It should not include such an exhaustive list of plays, many of which are not in place or even contemplated yet.

For a more mature records management program, it may make sense to group plays into categories, so they are easier to access and manage. Here are some broad categories of records management plays—but there are a couple of points to keep in mind. First, each of the categories below may include several to many individual plays.

Second, some of these categories may not seem specific to the records program, but the individual plays would. For example, plays under the decommissioning legacy systems category would focus on records appraisal, disposition of legacy records and information, and so forth.

Finally, this list does not include any standard management or project management plays, which are also necessary and may be part of the records management program, such as budgeting, defining business requirements, marketing and championing records management, records management system administration, and so forth. Potential categories of records management plays for the playbook:

- Capturing and filing records

- Digitizing paper records

- Responding to requests for records

- Conducting records, information, system, and process inventories

- Developing metadata and classifications schemes

- Maintaining the records retention schedule

- Applying retention and disposition

- Reviewing and updating governance documents

- Migrating records

- Decommissioning legacy systems and user information stores

- Remediation of redundant, outdated, and trivial information

- Evaluating systems for records management capabilities

- Change management

- Assessing and auditing the records management program

Depending on your organization and approach, you might also include “records management-adjacent” plays such as privacy and data protection, e-discovery, archives, or document control.

The Appendices

Appendices can include anything that would be helpful to those using the playbook to sustain the records management program. For example, if your organization has conducted a maturity assessment, such as the one aligned to the ARMA Information Governance Implementation Model, the results could be included as an appendix. We mentioned earlier the possibility of including a full RACI chart with contact information as an appendix. A full list of references and resources might be helpful as well—not just organization-specific resources like policies and procedures, but also things like industry standards and reference works. A glossary and list of acronyms and abbreviations may also be of value.

The Structure of a Records Management Play

Each play should include several standard elements. This makes it easy to maintain them and to add new plays over time.

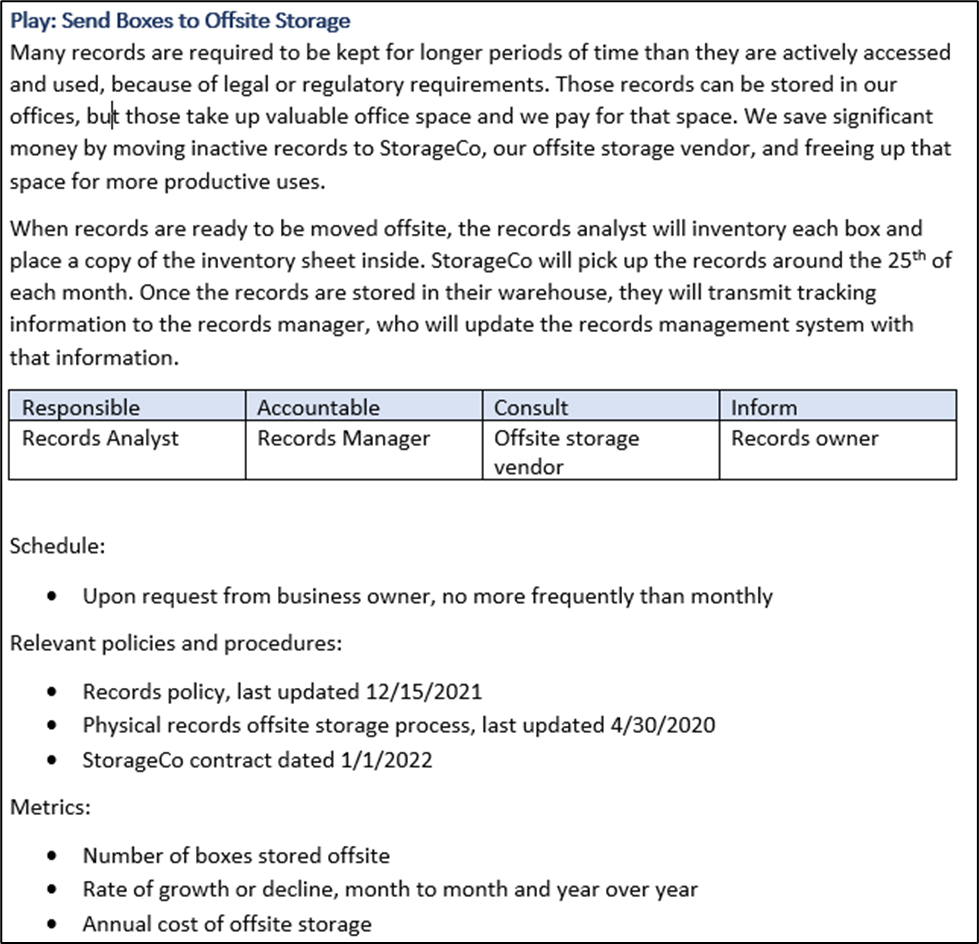

Name. This is the name of the play and should take the form of “verb-noun,” e.g., “Send Boxes to Offsite Storage.” Make sure that the name accurately describes the play using your organization’s terms.

Purpose. Why is this play in the playbook? What is the business value of executing this play?

Description. The overall description of what is required to execute the play. This should include enough information for someone new to be able to follow the steps in the play but should not necessarily be a fifty-nine-step checklist—rather, it should describe the intended outcomes. If there is a fifty-nine-step checklist, we can link to that in the references below.

Players or responsibilities. The play should identify the primary role responsible for executing the play. Since different plays will have different players, I like adding a mini-RACI chart for each play, and then rolling up all the individual RACIs into a full RACI chart either at the start of the playbook or as an appendix. It is up to you whether to include a point of contact—for maintenance purposes, it may be easier to include contact information as part of the full RACI chart if you create one.

Cadence. This refers to both the frequency of the execution of a play as well as the actual timing. For example, your “Send Boxes to Offsite Storage” play might be done every month, but only once a month, and only at the end of the month.

References. List all the things that can support the efficient and successful execution of a play: policies, procedures, guidelines, checklists, templates, standards, job aids, etc. If you can link to these so they are immediately available, even better; some ideas follow in the section on building the playbook.

Metrics. As the old management truism states, “if you can’t measure it, you can’t manage it.” Every play should have at least one metric that is relevant to how and why it is executed and that aligns to the overall goals of the organization. These should be quantifiable to the extent possible, and if you can get a financially quantifiable metric, that is even better.

Here is an example of an actual playbook play.

How to Build the Records Management Playbook

The actual process of building a playbook is fairly straightforward. The two key challenges are in determining what plays to include and what platform to build it on.

Determining What Plays to Include

As noted throughout, the plays in your records management playbook should include only those that you execute regularly. But responsibilities and documentation are often scattered across roles and information stores. First, start by reviewing any existing documentation of your records management processes—SOPs, flowcharts, procedures, etc.

Next, review any reports or other paperwork that you generate on a regular basis. These will often help to inform the metrics as well.

You should also review any existing job aids—checklists, glossaries/lists of terms or acronyms, naming convention cheat sheets, and so forth. Do not overlook the records policy and retention schedule—while these are the source of a few plays themselves, the retention schedule in particular often documents other records management-related tasks that result in the creation of records.

Look at job descriptions for the roles on the records management team—but make sure to compare them to the work that the members of the team are doing. Performance reviews can offer value as well, by identifying current expectations and priorities and potential gaps.

Finally, if you are just starting this process, a note of caution. Records management textbooks are a rich source of information, but they could lead you to developing and including many plays that you are just not doing. This can call the value of the playbook into question.

Where Should You Build Your Playbook?

Playbooks can be built as Word-type documents, as spreadsheets, or as PowerPoint-type presentations. There are tools designed for playbooks and similar types of authoring. A wiki can be a great way to build a playbook—each play is its own article, with links to related plays and to all the references and supporting materials.

But the platform and its attendant capabilities do not matter as much as the answers to these questions:

- What platform is easiest to access and use for those who will be using the playbook?

- What platform is easiest for the team to maintain the playbook?

If users cannot use it, or if the team cannot maintain it, it will become shelfware just like the traditional SOP manual.

Who Should Build the Playbook?

You! Well, you and any other subject matter experts who can describe the plays and their individual components. Again, in smaller organizations or records management programs this might be the single person running the program; in a larger organization or with a broader playbook, you will need to identify the right people to weigh in.

You will certainly also want to reach out to anyone identified as having a records management responsibility (e.g., through the RACI chart) who is not a formal member of the records management team.

Maintaining the Playbook

We have stressed throughout this article that the playbook is a living document that needs regular care and feeding to remain relevant and useful. Change is a constant; changes to technology, changes to legal or regulatory requirements, and changes to how the organization does business all require that the playbook be regularly reviewed and updated. In fact, reviewing the playbook should be a play in your playbook!

When the team finds out about a change that will impact a play, someone should be assigned to update the play with a timeline. Similarly, if the team determines a need for a new play, it should be assigned and scheduled. For example, developing a retention schedule the first time is a project. But reviewing and maintaining it are plays; once the retention schedule is finalized, those plays should be defined and added to the playbook.

Conclusion

The playbook is a great way to take your program to the next level. It takes some work up front to ensure that it is complete and accurately reflects the way your program works today, but once you have it, you will never look back!

[1] https://www.indeed.com/career-advice/career-development/what-is-a-playbook-in-business