Migrating Legacy Records – a Case Study

Organizations that maintain electronic records systems may at some point need to undertake either a records conversion or migration to address software obsolescence. This article discusses how the Calgary Police Service’s (CPS) records and information management (RIM) and information technology (IT) teams collaborated to ensure that nearly four million criminal case file records stored in its legacy system – a system used for more than 40 years – were successfully migrated to a new, off-the-shelf records management system (RMS).

Migrating the criminal case file records presented a number of challenges. First, the migration process, its planning and execution, had to comply with the CPS’ recordkeeping requirements as specified in its RIM program. As well, the migration had to preserve the integrity, authenticity, reliability, and usability of the records to be migrated.

Second, it was imperative that CPS’ case file records meet legal admissibility requirements for court purposes. Migrations involve risks such as records loss, deterioration, or corruption, which had to be managed to make certain the records admissibility was not jeopardized.

To ensure the recordkeeping and admissibility challenges were met, the RIM team applied two standards to direct the migration process:

- Canadian General Standards Board, CAN/CGSB 72.34-2017, Amendment 1 (October 2018), Electronic Records as Documentary Evidence (CAN/GGSB 72.34).

- International Organization of Standardization, ISO 13008, Information and Documentation – Digital Records Conversion and Migration Process, 2012 (ISO 13008).

Legal Requirements for Admissibility in Court

CPS’ RIM program has been based on CAN/CGSB 72.34 since 2005. The standard’s primary principle is that organizations must always be prepared to produce their records as evidence. Additionally, continuous compliance with CAN/CGSB 72.34 is a crucial component of the proof of the integrity of an electronic record or records system:

Use of an electronic record as evidence requires proof of the authenticity of the record, which can be inferred from the integrity of the electronic records system in which the record is made or received or stored, and proof that the record was “made in the usual and ordinary course of business” or is otherwise exempt from the legal rule barring hearsay…

With that said, according to the standard, records can be declared authentic if the integrity of the records system in which the record was made, received, or stored can be proven and/or if the reliability of the recordkeeping processes can be demonstrated.

Recordkeeping Requirements

Migration preserves digital records. ISO 13008 advises that the migration process must be managed to prevent any degradation or loss in the authenticity, reliability, integrity, and usability of the records. Documenting the recordkeeping requirements is also essential to the migration process. And, equally important, the personnel central to the process must be aware of the organizational requirements so they can ensure the records’ content, context, and structure are maintained. According to CAN/CGSB 72.34, the onus is on the organization to make certain its recordkeeping processes are reliable to protect and maintain the evidentiary and admissibility value of the records.

Applying Standards to the Migration Process

Why were standards applied? Standards consist of principles, procedures, methods, and practices usually developed by industry subject matter experts. Organizations that apply standards to their RIM programs generally do so on a voluntary basis. Standards promote efficiencies and effectiveness, and to the RIM team they signified best practices as the team focused on the required elements and defined the framework to achieve efficiencies, create economies, and improve the quality of the process.

CPS Case File Records Context

Calgary, Alberta, has a population of approximately 1.3 million. Since 1885, the city‘s law enforcement has been provided by the CPS, which now employs more than 2,000 sworn and 700 civilian members. The police respond to an average of 500,000 calls for service annually; of those, more than 100,000 calls become case file records, forming one of CPS’ most valuable records series.

This records series includes victim, suspect, and witness personal identifiable information; the full details of the occurrence, case, or incident; plus arrest reports, vehicle information, court documents, criminal charges, and other relevant information required as evidence. Each criminal case file record is identified by a unique case file number.

The legacy system maintained criminal case file information according to CPS’ records retention schedule. Records for major cases, such as homicides, sex crimes, and robbery, are permanently retained. Those for minor cases, such as breaking and entering, criminal traffic incidents, and domestic conflict, have a 40-year retention, while records for minor traffic cases are kept for 10 years. Over the years, IT performed many modifications and upgrades to ensure the collection and preservation of relevant police information was maintained, but some years ago it was evident the legacy system’s life cycle was nearing decommissioning and the legacy information would have to be migrated.

The Checklist Approach

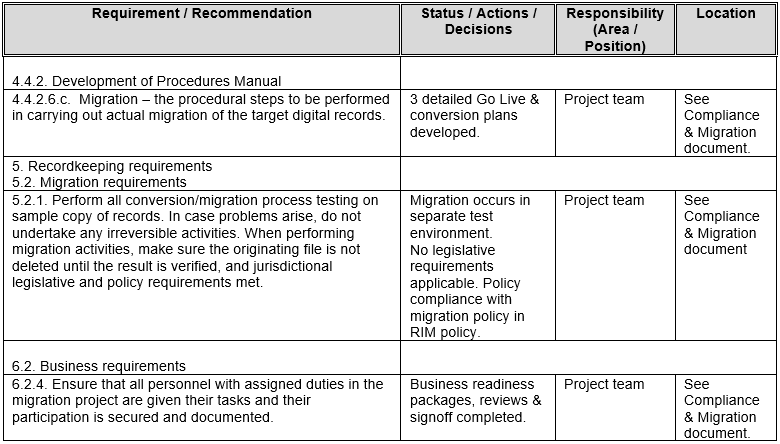

How are requirements and recommendations identified in the standards? The language of standards uses “shall,” “should,” and “may” statements. “Shall” denotes mandatory requirements; “should” is a recommendation; and “may,” is an option. The RIM team, which included the records manager and the information management coordinator, designed the spreadsheets to identify the applicable requirements and recommendations in each standard – see Figure 1 – and how the organization responded to them.

In Figure 1, the requirements and recommendations column is followed by columns addressing the status/action/decision required to complete the requirement, who or what area was responsible, and the location of the documentation generated in support of the criteria, such as mapping activities, planning documents, screen shots, workflows, decision documents, flow charts, logs, risk assessments, procedures, and other relevant documentation.

The IT team: the database administrators, and the project team (composed of the readiness team, data migration team, quality assurance, UAT, etc.), were responsible for updating the checklists, which were completed primarily by the project team. The project team had both internal personnel and consultants. To protect the security and confidentiality of the information and the integrity of the organization, personnel are security cleared and polygraphed.

Revisions to the checklists required both the IT and RIM teams’ agreement, with approval from the project manager; final sign-off was given by the superintendent whose area was responsible for the migration. The teams met regularly to discuss the checklist process and any challenges they were experiencing.

If the IT team was not able to speak to a requirement or recommendation, it provided the reason. For example, CAN/CGSB 72.34 specifies organizations are obligated to preserve recorded information as soon as litigation is contemplated or foreseeable. Because there was no litigation, and none was anticipated during the migration process, the IT team correctly noted that this requirement was not applicable.

Both standards require that all phases of the migration process are addressed in an approved procedures manual. CAN/CGSB 72.34 specifies the manual must outline detailed procedures ensuring that the records’ structure content, identity, and recordkeeping metadata are captured. ISO 13008 states that the procedures manual is designed to mitigate risks and to control the migration process targeted at preserving the integrity, authenticity, reliability, and usability of the records. In compliance with the standards, the teams documented the planning, testing, migration, validation, sign-off, and documentation phases of the migration process (see the side bar).

According to ISO 13008, the records migration process must address the following phases:

– Planning – the procedural steps, methods, people, and other resources to execute a successful migration.

– Testing – tests required to verify the planned procedures yield a successful migration.

– Migration – procedural steps to be performed to carry out the actual migration.

– Validation – procedural steps used to verify that records are successfully migrated.

– Sign-off – authorizations required to verify the migration was successfully completed in compliance with approved policy and procedures.

– Documentation – details records of the migration during each migration project.

Applying Checklists to the Migration Process

The IT team depended on checklists to help assure a successful migration and used them as step-by-step tasks to meet the requirements of all phases. Importantly, the components of the lists also revealed what “done” was, which helped the team start with the end in mind, knowing what the project completion should look like. Essentially, the checklists made the final goal accessible.

Figure 1 provides three examples of applying the checklists to the migration process. For example, point 4.4.2.6.c addresses the procedural steps to be performed for the actual migration of the records. The IT team described three detailed “go live” plans, which formed part of the documentation for the migration. These plans, the Soft Go Live, Service Go Live, and Case Conversion, were included in the movement of the historical cases from the legacy system to the RMS.

The second example, 5.2.1, requests that migration process testing be performed on a sample of the records. In response, the IT team created a data conversion environment to test data migration between systems using a small subset of data. The data was migrated to the new environment and tested by the QA team. The environment was wiped and a complete remigration occurred.

At each step of the migration, reconciliation points were required that had to balance between source and target. The balances on reconciliation, data content, and quality were tested by an independent party walking through a manual comparison between the old and new systems. A percentage of different case types was selected randomly for this testing. Finally, a dry run was completed into the actual production environment. The “go live” did not occur until all data was successfully migrated following a detailed cutover plan into production and the process of migrating and verifying was 100% accurate. Once signoff was completed on the dry runs, a go/no go was completed.

Lastly, point 6.2.3 focuses on the stakeholders and users of the records system and their level of involvement. The IT team prepared business readiness packages, reviews, and signoffs ensuring that an example of the packages was included as part of the migration documentation. The team defined readiness as business processes that were validated and accepted by business areas. All employees were trained and able to perform their specific jobs, and, if appropriate, the areas were engaged in testing their specific functions. Stabilization and sustainment measures were developed and implemented through partnerships with the different areas. Communications were prepared to be disseminated throughout the organization when the production environment was ready.

The Migration Process

All case file information in the legacy system that was to be migrated (for example, victim, accused, and witness names, addresses, telephone numbers, charges, vehicle license plates, and more) was logged and associated to the case file’s unique case number. This information was replicated into an SQL database, and counts were taken (total number of names, total number of addresses, telephone numbers, etc.). The populations were compared and tested to the information in the legacy system. Volunteers helped validate the sample quality of the content, creating detailed records of each test. All documents that were generated to describe the migration process were captured in the Compliance-Conversion and Migration document.

In terms of the timeline, the RIM team delivered the checklists to IT in early 2015; the migration was completed in late 2016; and all documentation was finalized by year-end 2017 and permanently stored in CPS’ electronic document and records management system.

The migration was scheduled for a weekend in order to reduce disruptions to the business. On that day, a systems outage was necessary to execute the process. Due to operational concerns and dependencies on CPS information by the police and its partner agencies, the systems could not be kept down for a long period. Coincidentally, just as the team was about to begin the migration process, a police action occurred and the migration had to be delayed for a short time.

Despite the minor set-back, the migration of more than 3,900,000 case file records was successfully executed. While the checklists directed the process, it was the IT team’s efforts, energy, skills, and persistence that ensured the recordkeeping and admissibility requirements were met throughout the process.

Success Achieved!

The RIM team defined success in a number of ways – for instance, having the legacy records migrated in their entirety, while preserving their integrity, authenticity, reliability, completeness, and usability. All recordkeeping and admissibility requirements had to be met in compliance with the standards, and the risks – such as records loss, deterioration, or corruption – had to be mitigated. Additional signs of success were ensuring that all checklists were referenced throughout the project planning stage and that the required documentation was produced during the testing and execution phases.

Owing in part to the IT team’s thorough capture of the requirements and fastidious monitoring of checklists, the RIM team’s definition of success came to fruition once the records were migrated according to the foundations the team thoroughly researched and itemized. From the beginning, the RIM team provided clarity of purpose and made recordkeeping processes accessible to the IT team in layman’s terms. Providing oversight to the entire process, the RIM team assured and delivered open communications, which clearly resulted in positive long-term effects.

Lessons Learned

In evaluating the migration process, the RIM team found that in its eagerness to capture the requirements of CAN/CGSB 72.34 and ISO 13008 in the checklists, there were elements of repetition because both standards discussed similar requirements. But, since it was vital to capture and address all tasks, the team decided it was more beneficial to over-represent than to under-represent the requirements.

While the entire migration process was an invaluable experience, it demonstrated that the requirements provided in both standards substantiated that there were no gaps in capturing the RIM functionality that addressed recordkeeping and admissibility criteria. IT responded positively in ensuring that the records were court-worthy and their content, context, and structures were in compliance with the standards. The checklists were pivotal to the migration process because they kept the tasks and project work on track, managed the risks, provided the requirements status (whether completed or outstanding), and controlled all processes.

Photo by bruce mars from Pexels

Download the PDF version of the article.

[ls_content_block id=”896″]

[ls_content_block id=”740″]

About the Author