Chronicle of a Records Manager: Controlling the Chaos of Disaster Response and Recovery

In the field of records management, there are logistical and large-scale projects that can challenge and perplex RIM professionals. These undertakings require planning, communication, documentation, and collaboration to be successful. In some instances, a RIM professional knows a project is imminent and has time to prepare. In other cases, a project may arise unexpectedly, forcing a RIM professional to use the knowledge they have acquired throughout their career forthwith, instead of planning ahead. Some projects may require the advice of professionals who have managed a similar project in the past. I have overseen two significant projects: an electronic discovery production and disaster response and recovery effort. This article will focus on the latter and will reflect on my experiences, observations, and insights as well as the trials and tribulations of the project.

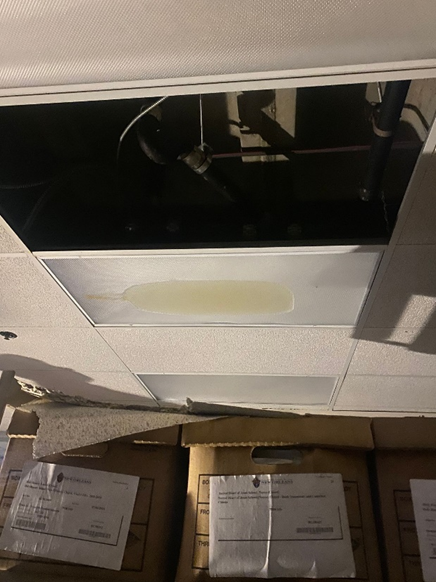

On the 29th of August, 2021, New Orleans felt the impacts of Hurricane Ida. The category four hurricane inundated the city with wind and rain. The unrelenting hurricane severely affected the 12-story office building of the Archdiocese of New Orleans (ANO) located in the Central Business District of the city. The building ultimately lost over thirty windows, causing significant wind and water damage throughout many of the twelve floors. The following image was taken by Dr. Emilie Gagnet Leumas.

The Office of Archives and Records (OAR) is the official repository for the records of the ANO. This department is responsible for developing and monitoring an efficient records management program as well as the identification, collection, description, protection, and availability of the historical records of the archdiocese. This office holds and maintains records created from the early 1700s to today.

Background

I have been a member of the OAR staff at the ANO since March 2013. I began as a Processing Archivist/Records Analyst. In 2018, I became the Senior Processing Archivist/Records Analyst. Then, in January 2021, I assumed the position of Director of Archives and Records, making me the Records Manager and Archivist of the Archdiocese of New Orleans. My responsibilities include creating and maintaining RIM policies and procedures concerning access, maintenance, retention, preservation, and arrangement of all business and archival records. I also serve as the administrator of the enterprise management system, and in situations such as this, I manage disaster response and recovery efforts.

The OAR has three locations. One location is at the Chancery and includes a vault that holds our oldest and most precious historical records. The Old Ursuline Convent in the French Quarter has an office, archives, and an exhibit space. This report focuses on the ANO site in the Central Business District at 1000 Howard Avenue. The OAR encompasses three floors of this building: floors four through six. These floors contain offices, a record center, a library and researcher area, a processing area, and the archives.

Hurricane Ida Preparations

On August 27, 2021, the OAR staff worked on hurricane preparations. These included:

- Calling churches within the boundaries of the ANO in low-lying areas to ensure they were evacuating their historical and business records either to a safe place or to the office on Walmsley Avenue for storage in the vault.

- Ensuring all churches were emailed the Archdiocesan Hurricane Preparation Handbook.

- Covering all computers and file cabinets in plastic sheeting.

- Moving all boxes, books of value, documents, paintings, pictures, and historical objects out of areas with non-boarded windows into the hallway, foyer, or other enclosed areas and placing them on tables to avoid water damage.

- Placing framed pictures on the floor once the tables were full.

These preparations took place on all three floors used by the OAR. I have followed these procedures for several hurricanes but had never previously needed them. This time, however, the situation would warrant all the preparations, and they would ultimately not be enough.

Alerted to the Damage

On the afternoon of August 31, I received a call from the previous director of OAR, who remains a consultant for ANO. She was at the office on Howard Avenue. Standing outside, she could see that several windows had blown out of the building, and it seemed that at least three were on OAR floors. She proceeded to enter the building and investigated the damage to the sixth and fifth floors but was unable to gain access to the fourth floor. After leaving the building, which was without power, she called me to lay out the situation. It was grim. The storm blew out two windows on the sixth floor, leaving my office and the lunchroom in complete disarray and saturating the carpet throughout most of the floor. Several boxes in the foyer had fallen over and were wet. Ceiling tiles had fallen in several rooms. On the fifth floor, part of the ceiling in the library had collapsed on top of archives and records that sat on top of the research table away from the windows. The floor had a significant amount of standing water, and there was some water on the floor within the archives. Both floors were hot and humid from the lack of air conditioning. Hearing this news and seeing her photos of the damaged building, my heart sank. I had thought that the building and collection would make it through Ida without an issue, but I had been very wrong. There was no time to panic; there was only time to alert executives, devise a plan of action, load up on supplies, head back to town, and start the grueling process of disaster response. The drive from West Monroe, Louisiana—where I had evacuated with my family—to New Orleans was a whirlwind of calls, planning, fears, and tears. The calls I made and received included speaking with the FEMA coordinator for the affected areas, our insurance coordinator, the insurance logistics coordinator, the chief financial officer, the Director of Archives and Records and Chancellor of the Diocese of Baton Rouge (DARBR), a disaster response and recovery specialist, and the staff processing archivist (archivist). The plan was to meet the insurance coordinator at the Howard Avenue office at 8:30 a.m. the next morning to assess the situation and devise a plan to address the identified issues.

Assessing the Damage

There is no way to fully prepare for what you may encounter when entering a powerless building after a hurricane. On the initial walk-through, I brought a phone with a camera, a headlamp, a notepad, and two pencils. I knew from previous education and training that documenting damage before moving or addressing anything was critical. I used the pictures and notes I wrote throughout the response and recovery to produce the damage and loss report as well as this article. I was aware that I would need documentation on damage and losses for insurance and internal purposes. The archivist and I met the insurance coordinator and the disaster response contractor at the site to do a walk-through and assess the damage.

When our walk-through concluded, I participated in a conference call with the insurance coordinator, CFO, and disaster response contractor. The insurance coordinator proposed stabilizing in place. It seemed inevitable that mold would become an issue with no power, wet carpet, and blown-out windows. Temperatures were in the mid to high 90s, and the RH was in the mid-80s—an ideal environment for mold. I wanted to move the collection as soon as possible. The CFO asked if the disaster response company could board up the windows, and the contractor confirmed they could. Even with a plan of boarding the windows, the CFO was remiss to leave the collection in place, as was I. We agreed that I would begin looking into alternative storage for our archival records while the person leading insurance logistics would look into other space options for our business records.

Stabilizing or Moving

After the insurance representative and contractor left, the archivist and I began creating an inventory of holdings in jeopardy. The DARBR set up a conference call with the archivist from the Louisiana State Archives. I gave them an assessment of the damage and outlined how much space we needed. The State Archives offered to take in up to 3,000 boxes of records of historical significance to Louisiana, including oversized objects. It seemed to me that moving our historical records to the State Archives was a reasonable option. The location was within a reasonable distance, and we would still have access to the collection. The DARBR also offered us office space at her archival and record center facility, which was close to the state archives. This would provide us with space for an additional 700 boxes. This burgeoning plan seemed solid.

I felt that we needed to prepare to execute this plan by first determining what records we needed to transfer to the state archives. We discussed best practices for reboxing records adjacent to wet records. We agreed that it was best to rebox all boxes within two boxes of wet records in all directions. The archivist and I spent the rest of the afternoon selecting and marking boxes we wanted to move. While doing this, we discovered that a historic WWII uniform in our collection had mold growing on it. This detection was just the beginning of the mold saga.

Over fifty boxes of records were water damaged. Fortunately, The disaster specialist’s company had the capability to vacuum freeze-dry documents. Freeze-drying is a technique used to dry and restore books and documents that have water damage. The process involves using a special chamber with a high-pressure vacuum that sublimates the moisture in the documents. This method turns liquid water into a gaseous state, thus eliminating moisture, preventing or stopping mold growth, and averting any complications typical of water-damaged documents. This technique allowed me to focus on the other issues the collection was facing and decide how to handle the remediation of wet records at a later time. In order for the vacuum freeze-dryer to be of the greatest use, we needed to identify the affected documents, rebox them, label them with their content information, and inventory them as soon as possible. We sent seventy-four boxes total to undergo the freeze-drying process: forty-one damp boxes and thirty-three wet boxes.

A Change of Plans

That evening, I had a conference call with key stakeholders. They informed me that moving anything to the Louisiana State Archives or the Diocese of Baton Rouge would affect the insurance coverage on all archives and records holdings and thus a move was not advised or sanctioned. Moving forward, the insurance company would look for a place that was satisfactory to them for both historical and business records. This change of plans caught me off guard. I was muted during the call without explanation, which was vexing. At the end of the call, I felt my position and experience had meant little to the people involved in response efforts. The calls with the Louisiana State Archives and the preparations I had made to move the historical collection there was now a waste of time and effort. Worst of all, I felt that I was failing to do the one thing that a records manager must do above all else: protect the records. That call reinforced to me that moving forward, I was the only advocate for the records in my care. I needed to speak up and demand that they hear me. I knew what I was doing and what needed to happen; I was more of an expert and knew more about these records than anyone in the organization or anyone working for our insurance company. I had undergone training for this, and I knew it was time to step up and take control of the situation.

When I reflect on this call and the situation as a whole at this stage in the process, I realize that in order for a records manager to be effective, they need full support from their organization. The LSU CRIM program has instilled in me the importance of executive sponsorship and an organization-wide Information Governance (IG) framework. I ponder the difference in response efforts if the organization I work for had invested in IG practices and created what Smallwood defines as “a strategic framework composed of standards, processes, roles, and metrics, that hold organizations and individuals accountable to…secure [and] maintain” information. An IG team could have been integral in helping the response and recovery process to be understood and supported by the organization as a whole, instead of the archivist and I being what at times felt like the only advocates for our holdings and facility.

Communication Woes

Communication is paramount to the success of most projects. This is especially true in situations where many people of different backgrounds and skillsets who have not worked together are thrust into working toward the same goal. In this case, the goal was to stabilize conditions on three floors in order to mitigate any additional damage to the collection. The deficiencies in the chain of command and the overall absence of meaningful communication increased the stress of this situation while decreasing efficiency and overall effectiveness.

I was the first director of a department at the Howard Avenue location to have contact with the insurance representative and the disaster response contractor. Because I was on-site early on in the project, people I worked with propagated my contact information to many people who took part in this project as well as other response projects not concerning OAR’s three floors. This quasi-internal strife caused an even greater breakdown of communications in the form of withholding information from me on demolition and moisture maps. I chose to address the issue directly; I made it known to various contractors and workers that I was not in charge of overall property management and tried to remain focused on the issues I was responsible for addressing. As in many other areas of life, communication issues can slow down and complicate the response process. It is important to recognize and remedy these issues early on when possible.

Power Problems

Lack of power throughout the city was a major hurdle at the beginning of this project. Because the power outage was citywide, a great many organizations needed generators, cords, and power boxes. Home and business owners with water damage were seeking air scrubbers, fans, and dehumidifiers. The lack of available supplies and simultaneous increase in demand made these response necessities hard to come by. On day one, I made the need for these items clear to all relevant parties—our CFO, insurance, disaster response contractors, and subcontractors. I communicated that without power to run the dehumidifiers, air scrubbers, and fans, the conditions of the building would jeopardize the collection, mold growth would vastly increase, and the costs for mold remediation would exponentially increase as well.

After we found mold in a new location on the morning of Friday, September 3rd, contractors promised me power, running fans, and dehumidifiers by the late afternoon on that Friday. This promise was one of many instances of contactors overpromising and underdelivering. On occasions when certain promises made by the disaster response contractor were not met, it was best to remind the contractor of the exact statement previously made by them and inquire about the status of the promised outcome. Documenting who stated what, when, and about which key project helped me have the information on hand that was necessary to remind parties about what was originally promised. Despite the frustrating roadblocks we encountered, being loud or overly upset rarely helps change the status of a situation; I found that remaining calm and persistent about the promised outcome worked best. The metaphor “the squeaky wheel gets the grease” was applicable throughout this project.

I was a very squeaky wheel about the lack of promised generator power. They told me generator power would be available at 6 p.m., then 7 p.m., maybe by 8 p.m., and then tomorrow. Tomorrow was simply not acceptable for the collection, the chance of accelerated mold growth would be exponentially increased. I called the insurance lead, the insurance logistics coordinator, the disaster response contractor, the disaster specialist subcontractor, the Director of the Building Office, and the Director of Property Management. I outlined the situation, restated what they had promised, and reminded them of the additional costs incurred for mold remediation if the power to the fans and dehumidifiers was not available until Saturday. I was once again assured power was coming that night. I made it clear that the archivist and I would remain at the site until I could verify that the fans and dehumidifiers were running. I did not give up; I squeaked on, and at 10 p.m., the cords and power boxes arrived. At 10:30 p.m., I walked up the stairs and checked the status of the fans and dehumidifiers on all three OAR floors. At 10:45 p.m., after over ten hours of being on-site, the result they promised me hours before finally came to fruition.

If I had accepted that power was out of reach until Saturday, the mold situation, which was already on its way to becoming grim, would have been catastrophic to the historical archives and business records. I did not give up on my team, the collection, or my responsibilities. I rose to the occasion and advocated for the collection in ways that would have been beyond my imagination just one week before. Pushing continual communication with people and making sure they heard me played an integral role in this accomplishment. But there were still more roadblocks ahead.

Over the next couple of days, there were continuing issues with the power. There were faulty cords and boxes, and these issues were causing continual breaker issues. The contractors were quick to dismiss the issues. But the fans, air scrubbers, and dehumidifiers kept turning off due to these power challenges. When the site manager would not take the situation seriously, I went up the chain of command until someone did. That night at 11 p.m., there was an electrical engineer on-site looking into the issue. The next day, higher-capacity power boxes arrived, resolving the power issues. Again, being the squeaky wheel is what moved the project forward and helped us stay proactive rather than reactive. Images below include the original and upgraded power boxes and myself documenting the change of power box size.

Mold Mayhem

While communication issues were the thread throughout most of the complications I encountered during this response effort, the most formidable opponent was mold. An adversary to historical and business records feared and despised by archivists and records managers around the world. I knew that high temperatures and RH levels combined with broken windows and roof damage were ideal conditions for mold growth. No efforts to remedy these issues occurred for five days; even then, it was close to seventy-two hours before generator power was established and mitigation efforts began. As of Friday evening, the mold that we had discovered was very minimal and seemed contained to a WWII uniform jacket and two damp boxes. I was optimistic that we had started mitigation efforts in time to avert major mold issues. Unfortunately, I was wrong.

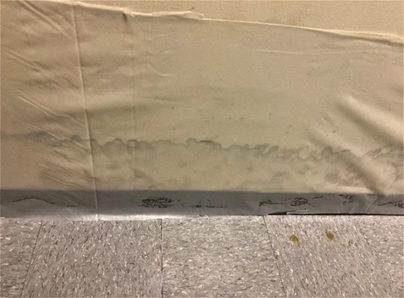

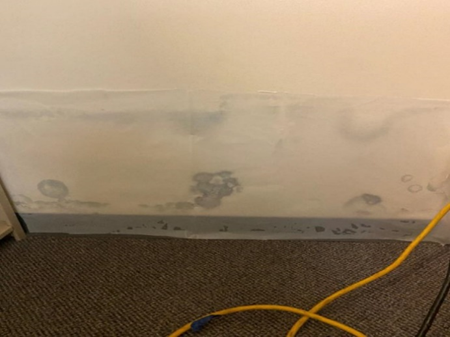

Mold on the fourth and fifth floors never became an issue, but the sixth floor had mold problems in several areas. This was likely because there was carpet throughout this floor, water saturating most of it. Carpet in a record center or archives is far from a best practice, but it was the situation I inherited when I became director nine months earlier. As soon as we identified the mold, I instated daily morning mold checks on all rooms on all three floors. This procedure led us to discover more mold almost daily for the next week and a half. After discovering any new mold, I documented it in my notes, took pictures, and reported the new growth to the site manager. He and I would do a walk-through of that area, and then the disaster crew would spray the affected area with an antimicrobial and cover it in plastic, which was the disaster company’s standard practice. The images below show mold discovered in various rooms before and after being covered by the disaster response team.

The disaster response contractor added air scrubbers to areas with mold due to their ability to remove and mitigate fine mold spores in the air. The mold gradually spread into hallways, closets, bathrooms, the kitchen, offices, and records rooms. We needed to move things away from the affected areas, an effort complicated by the fact that there were still no usable elevators. At first, we had to move all of the boxes in these areas down two flights of stairs with a crew of about ten people, including the archivist and myself. This task was arduous and did not thrill my team, especially since the building temperature was in the high 90s, but we had to complete it. As the days went on, elevator power and air conditioning came back online. At this point, the mold had continued to spread and we had to empty whole rooms.

Overall, we had to move close to 1,000 boxes, unboxed and unprocessed papers, and objects of various sizes from the sixth floor to the fourth. Due to mold exposure, we had to wipe down boxes with an antimicrobial spray or rebox them in hopes of ensuring the mold would not transfer to the fourth floor in the process. The archivist and I planned an assembly line and stocked it with needed supplies such as:

- Signs to denote where to put trash, exposed boxes, and clean boxes.

- Areas to wipe down and rebox.

- Sharpies, prebuilt boxes, and lids.

- Carts for affected boxes and carts for clean boxes.

- People staged on the sixth and fourth floors.

To ensure we promptly identified and mitigated new mold growth:

- We continued daily mold checks for a month.

- In the remaining rooms that held boxed records, we moved all boxes on the bottom row to the fourth floor to allow for a clear line of sight to likely mold spots.

- We kept a daily log of temperature and humidity for levels on all floors in multiple rooms.

Demolition

Eighteen days after Hurricane Ida damaged the Howard Avenue office, it was time to start demolition of the mold-afflicted walls. As with other stages of this project, communication was key to completing this task, and once again it was not up to par. First, I was not informed when the disaster company had slated demolition to start. This was due to a lack of transparency and an overall absence of a chain of command during disaster response and recovery situations. One afternoon, a new worker was on the fourth floor working on a computer. When I inquired about what he was working on, he told me he was creating a moisture map to determine where they would utilize demolition and weep holes. A moisture map or diagram “is a sketch of the property . . . represent[ing] a two-dimension drawing of affected and nonwater-damaged areas.” Moisture meters are a tool used to identify locations where elevated moisture levels suggest possible fungal infestation. When given access to the moisture map, I had some questions. The accuracy of the map and the meter used to create it concerned me. Some areas that had new mold growth were not identified as having elevated moisture levels, while they had listed areas with no mold and no visible water issues. While I understood that some water issues were not visible, I felt perplexed that the areas that I knew were exposed to excessive moisture and had visible mold were not listed on the map.

We determined that the disaster response team would need to remove two feet of drywall from walls with visible mold. Areas without visible mold but with elevated moisture levels according to the moisture map would have weep holes drilled into the bottom of the walls and they would set up flat fans to blow into the holes to reduce moisture. A weep hole is a passage for water to escape a building envelope and provide a place for the water to exit the building or wall. The research I have done, post use of weep holes at the site, outlines including these holes during the initial construction of a building, but a paucity of information is available as to the effectiveness of their use during disaster response efforts. Prior to my research, the contracted disaster response team told me it was standard practice to use weep holes during response efforts such as this.

On the sixth floor, there were seven walls with visible mold. Before the demolition started, we grouped boxes, card catalogs, display cases, and similar objects and covered them in plastic. The demolition crew completed the project quickly. Even though the original plan only included the demolition of walls with mold, the demolition crew decided to remove two feet from the walls identified on the moisture map without mold. The walls that were open on one side showcased the grim reality of the situation. The inside of several walls were heavily affected by mold even though they had zero indication of mold on the front side of the wall and were not denoted on the moisture map. We concluded that the demolition crew needed to cut out these walls as well. On the afternoon of this demolition day, I did a walk-through to document and assess the breadth of the devastation. The demolition crew had moved on to another floor while the clean-up crew uncovered the contents of the floor and started vacuuming. I took this as a sign that they had completed demolition and had removed all the mold-affected drywall. I began my quality check and to my dismay, there was still visible mold. The back of some walls that had noticeable mold still remained. The walls sprayed with an antimicrobial still had visible green fuzz. There were also backs of walls with visible mold that remained untreated. These findings concerned me and made me probe deeper into the situation. I got a flashlight and Sharpie and began lying down on the ground and looking up into the partially cut walls. I could see the mold growing on the inside of the walls; cutting out two feet was not enough. I put an X on the outside of all walls with mold visible on the inside of them. Once again, it was time to employ my squeaky wheel tactics. The images below show the mold issues inside of the walls on the sixth floor and the Xs I made on areas I identified with mold issues that had not been properly addressed.

I requested a meeting with the site manager right away. I also called the internal advisor of response and recovery efforts, informing him about my discovery and concerns, and he told me he was going straight to the top to make sure they correctly addressed these issues. I went back to the sixth floor and continued my internal wall checks. When the site manager and lead contractor arrived, we all agreed that a considerable amount of demolition still needed to take place. The contractors planned to cut some walls up to four feet. Again, they covered everything and brought the necessary machinery back up to the floor. When they finished the second round of demolition, they removed the plastic and an even more intensive cleaning ensued; a contractor quality check did not. I did do my quality check and made a few additional troubling discoveries. There was mold on the backside of a wall that went unaddressed, there was another wall that had the backside sprayed but not cut out, and mold was growing above the cut-out area on a couple of walls. This led to the third round of demolition and cleaning. These undiscovered issues by the contractor, lack of quality checks, and wasted time and materials underscored the overall lack of communication, clear procedures, and lack of quality work during this response effort.

Documenting

I cannot overstate the importance of documenting the entirety of the disaster response and recovery process. Documenting damage, mitigation, remediation, and communications with all stakeholders as well as the decision-making process are paramount to the success of response and recovery efforts. You will need thorough documentation of damage for insurance purposes, to qualify mitigation and remediation expenses, and to apply for response and recovery assistance or funding. When several people are working on different aspects of a project, it is important to document who is responsible for managing what duties and the overall timeline for completing each project. Documenting who is accountable for what aspect is especially important when response efforts overlap between groups. Documentation of damage can also help with planning response efforts by assisting with:

- Listing each problem and its scope.

- Analyzing each issue.

- Breaking each issue into parts.

- Considering possible solutions.

- Documenting and qualifying the chosen solution.

Taking bulleted notes in a notebook during water and food breaks worked well for me. I would go back through my notes in the evenings and elaborate on significant issues. I tried to document in real-time when talking with key stakeholders or when concerning issues arose.

Conclusion

Disaster response and recovery efforts can consist of chaos, elevated emotions, conflicting opinions, initially undiscovered damage, communication complications, and of course, the unexpected. Roadblocks can be preempted and moderated through preparation and planning, constant and effective communication, and thorough documentation throughout the response and recovery effort. It is important to remember that the road to success can contain several failures; you have to keep walking until you make it to an efficacious destination.

The top three lessons I have learned are 1) it is important to recognize what you do not know and find someone who does, as there is success in finding someone to guide you through a situation that you have not handled before. Utilizing the assistance of others who have been in a similar position and managed successful disaster response and recovery efforts themselves can be of great assistance to your endeavors. 2) After the first two weeks, I realized that you can never take too many pictures or document too much. Document as much as you can, including your decision-making process and reasoning, and organize it later; you never know when you will need it and find it beneficial. Data is the key to moving a project in the right direction and justifying your decisions; there is no need to guess if dehumidifiers are required and mitigating issues, for example, if you have the RH levels to prove it. 3) Communication is key to the success of most projects. In a disaster response situation, there is much to do and little time in which to do it before issues, like mold, intensify. Working together with stakeholders to create a road map to response and recovery, having set bi-weekly meetings, and creating an environment where communication is constant and productive will help enhance the effectiveness of response and recovery efforts.

When a project is complete, it is paramount to use what you have documented and learned to help strengthen your team and your organization’s disaster plan. You should take time to reflect on and analyze the successes, failures, acquired knowledge, and best practices utilized during the project. This reflection helps us grow and empowers us to help others navigate challenging projects in the future. Share your successes and failures with others in your field to help them prepare and flourish.

This paper was originally submitted to Louisiana State University as part of the Graduate Certificate in Records and Information Management program. The academic guidance of Dr. Tao Jin was beneficial to the success of this paper. My mentor Dr. Emilie Gagnet Leumas facilitated the knowledge and confidence I needed to navigate a disaster response and recovery. The Office of Archives and Records staff was integral during Hurricane Ida, especially Katie Vest, who was on-site and by my side during the entire project.

Dearstyne, B. W. (2006). TAKING CHARGE: Disaster Fallout Reinforces RIM’s Importance. Information Management Journal, 40(4), 37-43.

Disaster preparedness. (2021, January 27). Retrieved February 06, 2021, from https://media.ifrc.org/ifrc/what-we-do/disaster-and-crisis-management/disaster-preparedness/

Franks, P.C. (2018). Records and Information Management (2nd edition). ALA Neal-Schuman.

Leumas, Emilie Gagnet. Louisiana State University. Course LIS 7604 Principles of Records Management, Module 4: Emergency Management and Disaster Preparedness.

Moisture Detection and Moisture Mapping. Retrieved October 10, 2021, from https://http://preferredrestorationinc.com/moisture_diagram_and_mapping-1.pdftramexmeters.com/learn/moisture-detection-and-moisture-mapping.

Peterson, A. Disaster Planning and Preparedness. Knowledge and Content. Retrieved October 20, 2021, from https://www.lyrasis.org/content/Pages/Event-Details.aspx?Eid=FBDDBE1A-FF71-E211-960A-002219586F0D.

Smallwood, R. F. (2014). Information Governance: Concepts, strategies, and best practices. Wiley.

Water – dai: Fire & smoke restoration: Mold remediation experts. DAI. (2021, July 30). Retrieved October 1, 2021, from https://daillc.com/services/water-damage-restoration/.

About the Author

- Kimberly Johnson CRM, CA, PSM-I is a senior RIM consultant at NEOSTEK specializing in guiding organizations to implement RIM best practices and optimize ERM systems. In previous roles, she spearheaded crucial initiatives encompassing data governance, disaster response and recovery, and the intricacies of eDiscovery protocols. Kimberly's contributions to the field extend beyond her practical experience. She has shared her insights through publication, reflecting her commitment to advancing knowledge and best practices in Records and Information Management.

Ruben D Vargas

Great article and very useful information Kimberly Johnson!